April 20, 2013

The Anti-Oxidant Paradox and Its Implications for Interpreting Research

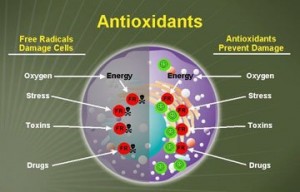

Antioxidant supplements continue to be touted by many fitness professionals as a nutritional panacea. In case you’re not aware, antioxidants are the body’s scavengers. They help to defend against damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) — unstable molecules that can injure healthy cells and tissues — which are produced in abundance each day during the normal course of respiration. The main culprit: oxygen. Every time you breathe, oxygen uptake causes ROS production. Environmental factors such as pollutants, smoke and certain chemicals also contribute to their formation. Their production have been linked to a multitude of ailments including arthritis, cardiovascular disease, dementia and cancer. Not surprisingly, exercise is associated with substantially greater ROS production given that it substantially inreases oxygen consumption. This has led to the supposition that antioxidant supplements are especially beneficial for hardcore exercisers.

Here’s a short-course in how the process works: Your body is made up of billions of cells held together by a series of electronic bonds. These bonds are arranged in pairs so that one electron balances the other. However, in response to various occurrences (such as oxygen consumption), a molecule can lose one of its electron pairs making it an unstable free radical. The free radical then tries to replace its lost electron by stealing one from another molecule. This sets up a chain reaction where the second molecule becomes a free radical and destabilizes a third molecule, which becomes a free radical and destabilizes a fourth molecule and so on.

To prevent rampant ROS production, your body has a sophisticated internal antioxidant system. Various antioxidant enzymes combine with antioxidants from the foods you eat to help keep ROS at bay. There are dozens of known antioxidants including Vitamin C, Vitamin E, coenzyme Q10, alpha-lipoic acid, and carotenoids, amongst others. Although these nutrients are readily obtainable from food sources, it is often postulated that it’s virtually impossible to consume adequate quantities from your daily diet, thus making supplementation mandatory. In theory, supplementing with antioxidants would seemingly make sense since a greater availability should allow for greater protection against ROS. Question is, does theory translate into practice?

I first became interested about the topic a dozen or so years ago. A friend gave me a book to read called The Antioxidant Miracle, which as the title implies touted the wonders of antioxidant supplementation. The book piqued my curiousity. I delved into the research. Lo and behold, the claims seemed legit. A large number of studies showed positive effects of supplementation on a wide array of health-related benefits. What really caught my attention was a review by Dekkers et al. in the journal Sports Medicine, which discussed favorable results of antioxidant supplements during intense physical activity. The article went on to conclude that “human studies reviewed indicate that antioxidant vitamin supplementation can be recommended to individuals performing regular heavy exercise.” At the time, I wasn’t very savvy as to the complexities of research. I jumped on the antioxidant supplement bandwagon.

My bad.

Fast forward several years. Larger randomized controlled trials were conducted. The findings of these studies were at best decidedly mixed, with a majority showing no health-related benefits from supplementing with antioxidants. Alarmingly, several meta-analyses reported that there may even be an increased supplement-associated risk for cancer, stroke, and all-cause mortality. An objective evaluation of the current literature would make it difficult for even the most ardent antioxidant proponent to make a case for improving well-being by supplementation.

What’s particularly interesting to me as an exercise scientist is emerging research suggesting that antioxidant supplements may actually have a *detrimental* effect on training-related adaptations, particularly those associated with muscle hypertrophy. At issue here is the distinction between chronic versus acute ROS production. Evidence does show that chronically elevated levels of ROS can impair muscle function and even bring about muscle wasting conditions. Understand, however, that exercise upregulates the body’s antioxidant defenses. This ultimately helps to reduce chronic elevations in ROS without the need for supplementation.

On the other hand, acute production of ROS during a workout has been implicated in a variety of exercise-related adaptations including enhanced muscle remodeling. ROS production has been found to promote growth in both smooth muscle and cardiac muscle, lending credence to the supposition that these substances may have similar hypertrophic effects on skeletal muscle as well. The mechanisms have yet to be determined, but studies show that ROS can function as key cellular anabolic signaling molecules in the response to exercise. What’s more, there is evidence that they help to mediate the activity of satellite cells, which are responsible for aiding in repair and regeneration of muscle fibers. I have covered these topics extensively in my recent reviews of the roles of metabolic stress and muscle damage in exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy. By suppressing ROS production, antioxidant supplements may inhibit these hypertrophic effects and thus impair the growth and repair process. Indeed, preliminary studies indicate a negative impact of supplementation on exercise-induced adaptations.

There are a couple of take-home messages here, the most obvious of which is that the risk/reward ratio for antioxidant supplementation appears to be poor. Focus on eating a diet replete in vegetables and fruits and you’ll get all the antioxidants you need to support basic health. Overloading on antioxidants via supplements will not confer any additional benefits; it’s possible they may actually cause harm. And although the jury is still out, it is at least conceivable that supplementation can impede muscular development and other exercise-related adaptations. Any way you slice it, antioxidant supplementation doesn’t seem to make sense, at least for otherwise healthy individuals who exercise on a regular basis.

On a broader scale, the overriding message to be gleaned is the importance of using caution when interpreting research. This is particularly true of exercise-related studies, which are usually limited by small sample sizes, the inability to control for various confounders, and the almost unlimited number of variations that encompass exercise program design. All-too-often fitness professionals are quick to form opinions based on limited evidence. Such an approach is decidedly misguided and unscientific. As illustrated here, I was guilty of falling into this trap. Fortunately I learned from the mistake and as a result became a more astute fitness professional.

Extrapolating research findings in an evidence-based fashion can be equated to solving a jigsaw puzzle. Each published study is a piece to the puzzle. In almost every situation there will be conflicting results between studies. Sometimes two studies will report diametrically opposite findings on the same topic. How can you make sense of all this?

The best fitness professionals, guys like Bret Contreras, Alan Aragon, Joe Dowdell, and James Krieger, will weigh the body of evidence by considering factors such as the type of study (experimental vs. observational), the subjects (animal vs. human), and the setting (in vitro, ex vivo, in vivo, etc). They’ll also take into account numerous other factors including study design, statistical power, generalizability, and the quality of the journal in which the study was published. Only after a thorough analysis of the prevailing body of literature can an educated opinion be formed that guides decision-making and provides the basis for practical recommendations. It’s a skill that can be honed. The more research you read, the better you become at critical thinking, allowing you to piece together the puzzle in question.

One last thing: I frequently hear trainers and even researchers cite a study as “proof” of a given opinion. Not! A single study never “proves” anything. Rather, it simply lends support to a given theory. As noted, some studies carry more weight than others. The greater the strength of evidence, the more support there is for the theory. But theories are not set in stone. Case in point: Until recently, it was taken as gospel that saturated fat and cholesterol caused cardiovascular disease. Every nutrition text, bar none, stated such as fact. Recent research has now challenged these assumptions, however, suggesting that any relationship is far more complex than previously thought. Bottom line is that the more knowledge we acquire, the more we realize just how much more there is to learn.

Always be skeptical. Always be willing to change your opinion based on new information. This is what separates the ordinary practitioners from the elite.

Cheers!

Brad

7 Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Entries (RSS)

Entries (RSS)

How about citing to the studies:

1. Larger randomized controlled trials were conducted

2. Alarmingly, several meta-analyses reported that there may even be an increased supplement-associated risk for cancer, stroke, and all-cause mortality

3. emerging research suggesting that antioxidant supplements may actually have a *detrimental* effect on training-related adaptations, particularly those associated with muscle hypertrophy

4. acute production of ROS during a workout has been implicated in a variety of exercise-related adaptations including enhanced muscle remodeling.

Your analysis might prove correct. But the audience of a “trusted source” and an “exercise scientist” expects studies (SOGTFO).

Comment by Piqued — April 20, 2013 @ 11:15 pm

Your words, overloading on antioxidants may be detrimental. Well what do you consider overloading. Are you saying , take no supplements? I don’t imagine too many of your cohorts would agree with you since so many of them sell these products. Now I’m totally confused, especially considering that I don’t grow my own organic foods to supply all the necessary nutrients.

Comment by Eugene Sedita — April 21, 2013 @ 1:36 am

Piqued:

Fair enough. I have linked references to substantiate my statements.

Cheers!

Brad

Comment by Brad — April 22, 2013 @ 7:49 am

Eugene:

First, you apparently took my comments out of context. I never stated not to take supplements; to the contrary, certain supplements definitely can be beneficial in the proper situations. The post was specific to high-dosages of antioxidants taken for prevention against disease. As far as the context for “overloading,” this refers to the dosages normally recommended for achieving a therapeutic effect from antioxidants. Such therapeutic dosages are the basis of the research cited in my post. Hope this helps.

Brad

Comment by Brad — April 22, 2013 @ 8:09 am

Good post, Brad.

Atleast for cancer, one of the 8 recommendations by ‘Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective’ is not to take any supplements to prevent cancer.

And Euegne, there is nothing saying organic supply “all” nutrients that regular foods don’t.

Comment by Anoop — April 28, 2013 @ 8:57 am

Thanks Anoop. I was remiss in not including you in the group of astute fitness pros who understand the nuances of evidence-based practice! Cheers 🙂

Brad

Comment by Brad — April 28, 2013 @ 9:13 am

My cousin and her husband work for a company pushing the anti-oxidants, making a lot of money from the alleged anti-ageing affects. Every time I go around to their house they’re talking about how the company is making breakthroughs and has launched a new product that is making hundreds of millions worldwide. I ask for links to peer reviewed research and get nothing.

Great article you have here Brad, but it saddens me when I come back to this and reread it sometimes.

Comment by Andy Morgan — August 1, 2013 @ 8:59 am